One might think fishing would be one of the least controversial industries but, sadly, that has not been the case for some time. We have just lived through the wrangling over Brexit and the end result isn’t very happy for many in the trade, not least because it seems well-nigh impossible to export live shellfish to Europe (except, it seems happily, from Salcombe, at least at the moment).

But fishing’s problems go back so much further than this. For some time it has been said that it takes a ton of fuel to catch and land a ton of fish. Partly that is because historically many of the fishing fields were far away, like Newfoundland, but also because boats are not very fuel efficient particularly in rough weather.

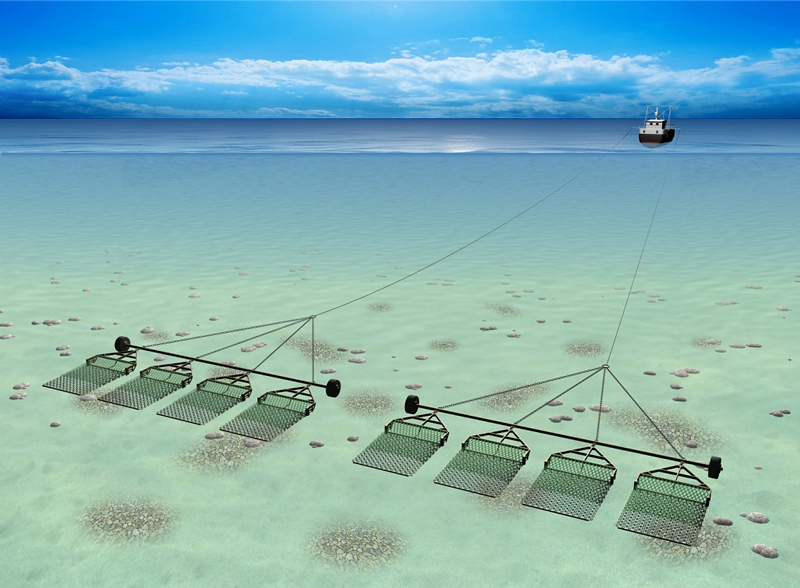

Then there were the issues over how to fish. Scraping the sea bed with steel crates, or beam trawling just above it, often leaves damage which can take years, sometimes decades, to heal. Huge nets trap lots of fish, including many which nobody wants and might even be endangered. Quotas are resented: they are allocated according to a formula which is derided, they prevent fishing boats going to sea and earning a living, and they give rise to wasteful by-catch which is thrown back dead and useless. And let’s not mention the quantities of fish which are caught simply to feed cats.

Then there were the issues over how to fish. Scraping the sea bed with steel crates, or beam trawling just above it, often leaves damage which can take years, sometimes decades, to heal. Huge nets trap lots of fish, including many which nobody wants and might even be endangered. Quotas are resented: they are allocated according to a formula which is derided, they prevent fishing boats going to sea and earning a living, and they give rise to wasteful by-catch which is thrown back dead and useless. And let’s not mention the quantities of fish which are caught simply to feed cats.

When Riverford’s founder, Guy Singh-Watson became energised after watching the Netflix documentary Seaspiracy, he went in search of a sustainable source of fish. It is no surprise that he concluded there isn’t one. Guy argues that if we can’t have marine conservation areas where commercial fishing is prohibited, if we can’t make disturbing the sea bed illegal, and if we can’t redistribute quotas away from huge (foreign) vessels to small, local fishing boats, then we should stop eating fish.

It’s difficult to disagree with this. For some years I chaired the charity which owns the foreshore at Hastings that is home to the largest beach-launched fishing fleet in Europe – about 25 small boats. This fleet is recognised for the sustainable way in which it fishes and – this is the important part – it has very strong fish stocks on its doorstep as a result. Moreover, instead of putting all its fish on the train to London, much is now sold locally so the fleet gets retail rather than wholesale prices for its hard work. Maybe smaller boats and local sales is one of the better ways forward for the fishing industry.

to the largest beach-launched fishing fleet in Europe – about 25 small boats. This fleet is recognised for the sustainable way in which it fishes and – this is the important part – it has very strong fish stocks on its doorstep as a result. Moreover, instead of putting all its fish on the train to London, much is now sold locally so the fleet gets retail rather than wholesale prices for its hard work. Maybe smaller boats and local sales is one of the better ways forward for the fishing industry.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.