Last time I planned to go to a performance by BalletBoyz it was, like so much else in the last two years, cancelled because of covid. I wasn’t taking any chances this time, so booked tickets for their one-night visit, on the day that booking opened.

I may be wrong, but I get a slight feeling that the average age of the company is creeping up just a little, as it becomes more appropriate to refer to them as men, rather than boys; but even if this is true, the dancers have lost none of their youthful vigour, strength and inspiration. So I was treated, once more, to a spectacular performance.

The first dance was ‘Ripple’, an hypnotically lyrical piece choreographed by Xie Xin. In this dance, the dancers became the sea, constantly moving, swelling and subsiding, especially through the movement of their arms. Although quite a bit of the dance was scored for the whole troupe, there were several duets, in which a hand would reach out towards the partner’s hand, only to be retracted before they could touch.

The first dance was ‘Ripple’, an hypnotically lyrical piece choreographed by Xie Xin. In this dance, the dancers became the sea, constantly moving, swelling and subsiding, especially through the movement of their arms. Although quite a bit of the dance was scored for the whole troupe, there were several duets, in which a hand would reach out towards the partner’s hand, only to be retracted before they could touch.

This was followed by ‘Bradley 4:18’, inspired by a poem by Kate (Kai) Tempest, and choreographed by Maxine Doyle with music composed by Cassie Kinoshi. Here there was much more evidence of male angst and of frustrated isolation, with a recurring motif of running full tilt around the stage, and ocasional desperate tearing off of garments. But there were also moments indicating trust and there was some resolution as the piece progressed. The footwork throughout was clean and dynamic, and the dance ended with a startlingly dramatic leap.

This was followed by ‘Bradley 4:18’, inspired by a poem by Kate (Kai) Tempest, and choreographed by Maxine Doyle with music composed by Cassie Kinoshi. Here there was much more evidence of male angst and of frustrated isolation, with a recurring motif of running full tilt around the stage, and ocasional desperate tearing off of garments. But there were also moments indicating trust and there was some resolution as the piece progressed. The footwork throughout was clean and dynamic, and the dance ended with a startlingly dramatic leap.

Both pieces started with film material, in which we saw the dancers rehearsing and the choreographers being interviewed about their work. It’s quite difficult to explain exactly why, but it seemed right to me that the choreographers of both pieces were women. Although the dances were full of boyish energy and masculine strength, there was also a certain grace and tenderness to the works, particularly in the more lyrical moments, that seemed to be particularly in keeping with a feminine creativity. That is not to say, of course, that such qualities cannot be found in male-created choreography; it was just that in these pieces, the focus had, for me, a feminine slant.

All the way through, the bodies appeared to have no weight, so that the men seemed to float off the floor or, as quite frequently occurred, slide effortlessly over it. Added to this was the astonishing flexibility of their bodies, raising the question as to whether they actually had any bones at all.

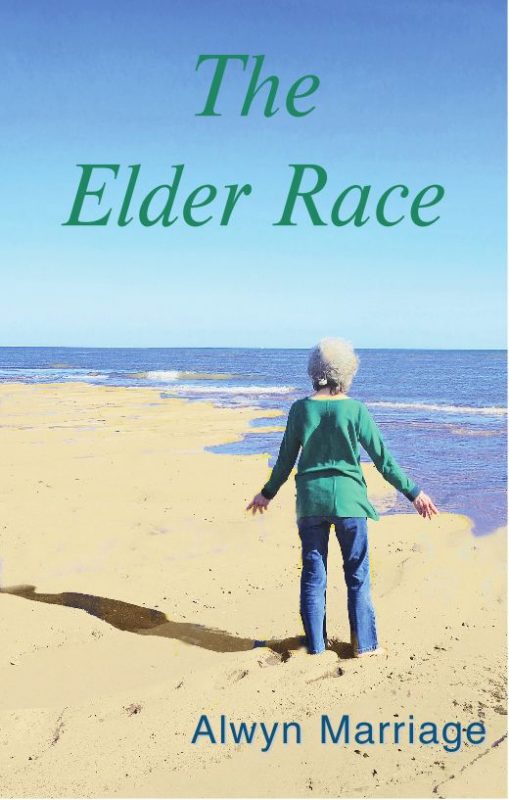

Those of you who are familiar with me or my writings will know that I am an enthusiastic fan of contemporary dance, which I feel is the closest other art form to poetry. The main character in my latest novel, The Elder Race, was a contemporary dancer, and I enjoyed writing about her recovery of agility and strength on a Cornish beach after a period in which she had had little opportunity to dance. I have a feeling that some of the BalletBoyz would have enjoyed the dances she choreographed to the accompaniment of the sound of waves and cry of gulls. In any case, I like to think so.