The poet, Jack Clemo, was born 100 years ago this year, into a poor, pious, working class family in the china clay area of Cornwall, which he described as ‘a fitting birthplace for me, being dwarfed under Bloomdale clay-dump, solitary, grim-looking, with no drainage, no water or electricity supply, and no back door.’ He was a bright, precocious child who could, apparently, recite the Lord’s Prayer at 18 months, and was reading fluently by 4. However, a few days before his 5th birthday, his eye troubles began. He became so light-sensitive that he had to spend months in total darkness, with his eyes bandaged. He suffered another bout of blindness when he was 12, and his eyesight deteriorated in the ensuing years, resulting, in 1945, in total blindness. He was, however, developing as a poet.

Deaf, blind, angry, poor and religious, Jack had difficulty forming relationships, but became convinced that God intended him to marry. The prospects for future marital happiness were not great, but then, in 1967, he received a letter out of the blue from Ruth Peaty, wanting to get to know him because ‘I think you are an interesting personality’. A strange correspondence began which led, the following summer, to a meeting and, on 26th October 1967, to Jack and Ruth’s marriage. During the following year Jack wrote more poetry than he had ever done before.

Deaf, blind, angry, poor and religious, Jack had difficulty forming relationships, but became convinced that God intended him to marry. The prospects for future marital happiness were not great, but then, in 1967, he received a letter out of the blue from Ruth Peaty, wanting to get to know him because ‘I think you are an interesting personality’. A strange correspondence began which led, the following summer, to a meeting and, on 26th October 1967, to Jack and Ruth’s marriage. During the following year Jack wrote more poetry than he had ever done before.

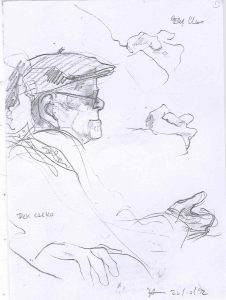

My own contact with Jack came about for two reasons. First, in the 1980s and 90s I was editing a journal called Christian, in which I always gave space to a wide range of good modern poets. Jack was a great friend of this journal, and over the years I published a fair number of his poems. Then I also included one of his poems when I edited the anthology New Christian Poetry for Collins in 1990. I was also Literature Coordinator at the University of Surrey at this time, where we had an Annual University Poetry Lecture in which one modern poet gave a lecture on another respected modern poet. There was no question of Jack speaking in public, so I invited Donald Davie to give the lecture, and Jack, Ruth and Ruth’s sister, Bella, came to stay with me and attended the lecture. The artist, Heather Spears, was present at the lecture and produced the wonderful drawings of Jack that I’ve included on this blog.

The relationship between Jack and Ruth was both tender and stunning. She was his eyes and ears, but he contributed a richness to her life as well. Neither was young when they met, and the development of their intimacy and trust was not cheaply won.

Oh darling, lead me safely through the world:

Make clear each sign lest my male clay be hurled

To flame when it seeks cooling, or to ice

When lava leaps in you, hot veins entice

Beneath a white breast I misread,

Thinking it cold, and pass unconscious of your need.

(Intimate Landscape, p 45)

How did one communicate with this great man? He could, of course, speak, though one had to bend towards him and listen carefully to catch his words. Then came the practice of speaking on his hand, tracing capital letters and spelling out each word until he grasped what one was trying to say. This unusual way of communication slowed conversation down to an extent, but it was intensely moving. I remember my first experience of communicating with Jack in this way, when I realised that here was an entirely different method of human interaction. It reminded me of the first time I encountered geysers and bubbling mud in New Zealand, when it dawned on me that I’d never see the ground beneath my feet in quite the same way again.

How did one communicate with this great man? He could, of course, speak, though one had to bend towards him and listen carefully to catch his words. Then came the practice of speaking on his hand, tracing capital letters and spelling out each word until he grasped what one was trying to say. This unusual way of communication slowed conversation down to an extent, but it was intensely moving. I remember my first experience of communicating with Jack in this way, when I realised that here was an entirely different method of human interaction. It reminded me of the first time I encountered geysers and bubbling mud in New Zealand, when it dawned on me that I’d never see the ground beneath my feet in quite the same way again.

His poetry, like Jack himself, is not always easy, and can be fierce and uncompromising. Given the dark Calvinism that coloured much of his life, he was unlikely to enjoy very wide popularity; but he was, and remains, one of the most interesting and talented writers of the 20thC. He wrote prolifically and continued to submit poems to me to consider for inclusion in Christian right up until his death in 1994 – and even after that, his widow, Ruth, sent me a number of poems that had not previously been published. In Jack’s late poems the anger and brutality of his earlier work has softened and there is a new gentleness and joy that reflects the changes in his personal life.

As well as his numerous poetry collections, Jack Clemo published two novels, two volumes of autobiography and a statement of faith. He was awarded a Civil List pension in 1961, an honorary D Litt from Exeter University in 1981, and he was crowned Prydyth an Pry (Poet of clay) at Cornish Gorsedd in September 1970.

My friendship with Jack left a deep impression on me, which was one of the reasons why I noticed a poetry competition in his name when it was advertised early this year. The specified theme was ‘wonderful things are about to happen – wildest things are about to happen’. In my poetry file there was a poem, Transition, that I’d written when I was Poet in Residence for the Winchester Ten Days Arts Festival (see blog November 5th 2013), which seemed appropriate, so I sent that in.

Just before I left Romania (see blog 18th May 2016) I received an email from the Arts Centre Group to tell me that I was one of three prizewinners in the Clemo competition, and inviting me to attend the prizegiving in May. When I turned up at this event in London, I still had no idea which prize I’d won but, as in the Oscars, we progressed from third prize to second to first. I was thrilled to be awarded first prize, and I know that Jack would have been delighted too.

Several people have asked for copies of the poem that won, so here it is?

Transition

Winchester cathedral

When we’re too tired or busy to even want to pray

and we’re conscious only of obstacles between us and where

the air is clearer, music played on strings or sung by a choir

can sometimes rise like incense, carrying our prayer.

Out above this soaring roof, beyond the city,

daylight and blessings are filtering down,

a skylark is pouring her heart out in rippling silver curtains

between a chalkland greensward and a great blue dome.

Something or someone is bridging the gap, inviting us

to swim up into what we don’t yet understand,

to take the risk of somersaulting into freedom,

to believe in the possibility of a listening ear,

to learn, like a violinist, to touch the string lightly,

absorb the vibrations and feel the harmonic soar.

Jack Clemo’s books

Two novels: Wilding Graft (which won an Atlantic Award in Literature from Birmingham University in 1948), and The Shadowed  Bed, which was written soon afterwards, but not published until 1986.

Bed, which was written soon afterwards, but not published until 1986.

Two volumes of autobiography: Confession of a Rebel (1949) and Marriage of a Rebel (1980); and his statement of faith, The Invading Gospel (1958).

His books of poetry were: The Clay Verge (1951), and The Wintry Priesthood (1951, which won an Arts Council Festival of Britain poetry prize). Both of these collections came together in The Map of Clay.

Then, in later life, the poetry collections came thick and fast: Cactus on Carmel (1967), The Echoing Tip (1971), Broad Autumn (1975), A Different Drummer (1986), Approach to Murano (1993, after visiting Italy) and The Cured Arno (1995 – completed shortly before his death in July 1994.